So the AI bubble is on everyone’s mind. I don’t have an answer on where that stands. However, I was around during the Internet bubble. In fact, I got out of my Wharton/Penn grad studies in mid-1999 to start my career in venture capital, and by March 2000, I was doing restructurings as co-investors in our deals exited the market or ran for the hills.

If you listen to CNBC at all, you will hear a recurring comparison about this market and how it compares to the Internet bubble. The rapid rise of artificial intelligence has been hailed as revolutionary, with many believing it will transform industries and daily life. We are currently experiencing an AI boom, marked by rapid investment, stock market surges, and economic integration driven by the AI industry. Looking at history, we see that past bubbles—like the dot-com boom, which ultimately led to the dot com crash, and the housing crisis—offer important lessons about overinvestment and market corrections. As we speculate about the future, it’s clear that AI has the potential to reshape the economy and society in ways we are only beginning to imagine.

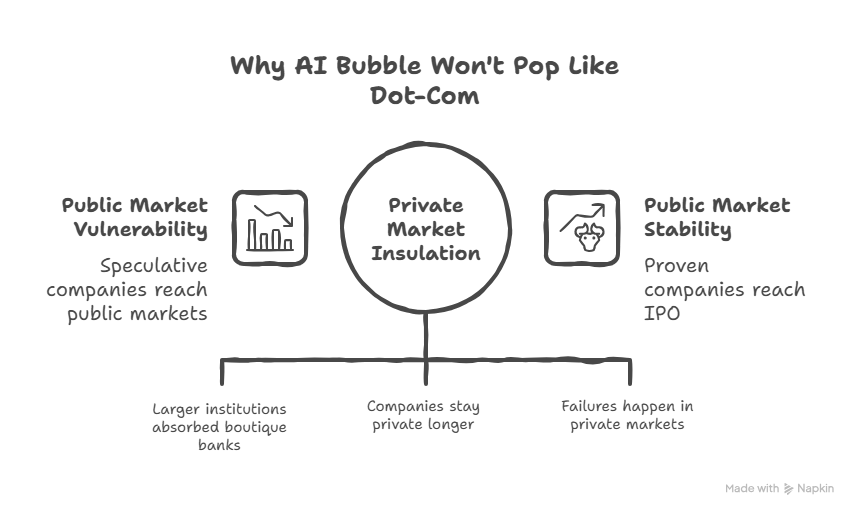

To say I have a point of view on this would be an overstatement; however, I do have a view on an overlooked difference in the capital markets related to venture-backed, high-growth companies that participated in each of these massive market valuation increases. Understanding these nuances gives some additional perspective about what’s going on and if a massive market correction this time will ever happen. Many wonder whether the current AI market will face a similar fate as past bubbles.

The key difference? The infrastructure that enabled thousands of speculative companies to reach public markets in 1999 no longer exists. The boutique investment banks that took early-stage companies public were absorbed by larger institutions by 2000. The venture capital market expanded dramatically, allowing companies to stay private three times longer. The Federal Reserve also plays a significant role in shaping market conditions and investor sentiment during both the dot-com and AI booms.

And the failures that would have been spectacular public blow-ups in 2000 are now happening quietly behind the scenes in private markets. As a result, if the AI reckoning is underway—you just won’t see it from your brokerage account. Personally, I think it’s still a bit early even in the private markets because the hold periods for venture capital investors are so long we are probably still in the early to middle innings depending on which cycle of AI these funds are invested in. To be sure, there is still money piling in and we may not understand the impact of that for another five to ten years, especially as AI investment is increasingly influencing the broader economy and attracting capital from around the world.

TL;DR: The dot-com bubble burst publicly because small investment banks took speculative companies public at 4-year median ages with zero revenue. Today’s 3-5x larger VC market keeps companies private until 14-year median ages with $500M+ revenue thresholds. Although, AI failures are happening but they’re hidden in private markets. However, public market investors are insulated from the carnage because only proven companies reach IPO. The structural plumbing of capital markets has fundamentally changed where speculation lives and dies.

The Dot-Com Era: When Anyone Could Go Public

To understand why this time is structurally different, you need to understand what made the dotcom bubble possible in the first place.

In 1999, the median age of a technology company at IPO was just four years. Companies went public with no established business models and often couldn’t demonstrate any path to cash-flow generation or profits. The dotcom bubble was characterized by a rush of companies with little to no profits entering public markets, fueling unsustainable valuations. The average price-to-sales ratio of companies that went public in 2000 was an almost unbelievable 48.9. Morgan Stanley’s internet analyst Mary Meeker tracked 199 internet stocks with a combined market capitalization of $450 billion—but total annual sales of only $21 billion and collective losses of $6.2 billion dollars. Analysts like Mary Meeker often mention the risks and signs of a bubble in their reports, highlighting the warning signs that were present even then.

This wasn’t irrational exuberance operating in a vacuum. It was enabled by a specific market structure that no longer exists.

During the 1990s, a group of boutique investment banks dominated technology IPOs. Known as the “CHARM Banks”—Cowen & Co., Hambrecht & Quist, Alex Brown, Robertson Stephens, and Montgomery Securities—these firms specialized in taking smaller, earlier-stage companies public. Hambrecht & Quist alone underwrote IPOs for Apple, Genentech, Adobe, Netscape, and Amazon. As an example of the speculative nature of the era, Netscape’s IPO in 1995 saw its stock price nearly double on the first day of trading, despite the company having minimal profits at the time. These banks had the expertise, relationships, and risk appetite to bring companies to market that larger institutions wouldn’t touch.

By 2000, every single one of them (except Cowen, I think) had been acquired by larger commercial or bulge-bracket investment banks. Hambrecht & Quist went to Chase Manhattan for $1.35 billion in 1999. The others followed similar paths. After the dot-com bubble burst, what happened was a rapid collapse of these boutique banks’ influence and the infrastructure that enabled speculative early-stage companies to access public markets largely disappeared.

The New Plumbing: Venture Capital as the Holding Tank

Into that void stepped an enormously expanded venture capital market.

In 1995, annual VC investment in the United States totaled about $7 billion. By 2000, it had surged to nearly $100 billion. That seemed massive at the time. Today, global venture capital investment exceeds $337 billion annually, with U.S. investment alone approaching $140 billion.

This 3-5x expansion in available private capital fundamentally changed the lifecycle of high-growth companies. When VC money was scarce, companies needed to go public early to fund their growth. When VC money became abundant, companies could stay private indefinitely, raising round after round without facing the scrutiny of public markets. Tech companies, including big tech and smaller companies, are now able to stay private longer due to increased investing and spending on AI infrastructure and innovation. Big AI firms are now able to dominate the market thanks to their access to vast capital and advanced infrastructure.

The numbers tell the story clearly.

The median age of a technology company at IPO was 4 years in 1999 while in 2024, it was 14 years.

Companies that would have gone public as speculative bets in the dot-com era now spend a decade proving themselves in private markets before ever facing public investors. Today, mature businesses with proven models and financial stability are the ones reaching IPO, in contrast to the speculative ventures of the past.

The threshold for going public has changed dramatically as well. In 2000, companies went public with no revenue. Today, the median revenue at IPO exceeds $500 million, with expectations of 30-40% year-over-year growth and improving free cash flow margins. Only a valuable company with significant revenue and strong growth prospects—often among the most profitable AI companies and tech companies—reaches public markets, having already survived a decade of private market Darwinism.

Where AI Stress May Already Be Appearing

This brings us to the current AI moment. If stress is building in AI investments, we likely wouldn’t see it in public markets first—we’d see early indicators in the private company data. And there are some signals worth watching.

Reports from Carta indicated a 25.6% increase in startup failures, rising from 769 in 2023 to 966 in 2024*.*

AngelList observed an even more pronounced rise of 56.2%, climbing from 233 failures in 2023 to 364 the following year. According to first-quarter 2024 data, startup failures in the United States increased by 58% compared to previous years, with 44% citing “running out of cash” as the primary factor. A significant contributor to these failures is the high cost of building and maintaining AI infrastructure, including expenditures on data centers and energy consumption. This raises concern about the sustainability of current investment trends and the potential risks of overvalued infrastructure assets.

The broader statistics suggest challenging unit economics across the sector: over 90% of AI startups fail within the first five years, and in 2023, more than 60% of AI tools built by startups had no recurring revenue or monetization path. The reality is that many investments lack a clear sense of profitability or sustainable business models.

Whether this represents the beginning of a broader correction or simply the normal attrition of a maturing technology sector remains to be seen. But if a reckoning does unfold, this is where the early evidence would appear—in private market data, invisible to the retail investors and cable news viewers watching public indices for signs of trouble. These private market corrections are essentially different from public market crashes, as they often go unnoticed by the broader public. Despite heavy investment, actual adoption by consumers remains limited, further widening the gap between expectations and real-world outcomes. At the same time, demand for professionals who have completed an AI course is growing rapidly, as companies seek to build in-house expertise and keep pace with technological advancements.

The Market Cap Comparison That Explains Everything

Consider this comparison: From 1998 to 2000, IPO proceeds totaled approximately $235 billion—against a total U.S. stock market capitalization of $17.6 trillion. That means IPO activity represented about 1.34% of the total market, with both billions and even trillions at stake during this period. During both the dot-com era and today, swings in market value have involved the movement of over a trillion dollars, underscoring the immense scale of these financial shifts.

From 2023 to 2025, IPO proceeds totaled approximately $88 billion against a total U.S. market capitalization of $67.8 trillion. That’s just 0.13% of the total market.

IPO activity represented roughly ten times more of the total market during the dot-com era compared to today. And remember—those dot-com IPOs frequently doubled or tripled on their first day of trading. The average Internet IPO in 1999 closed 90% above its offering price on opening day and ended the year at 266% above its offering price. Stock prices reached record highs, and the actual market cap impact was even more dramatic than the proceeds suggest. This helps explain why, when the bubble pops, the effects can be so widespread, as seen when the dot-com bubble burst.

Today, AI infrastructure spending—especially on data centers and GPU chips—is a major driver of U.S. economic expansion and is contributing significantly to GDP growth.

When those companies collapsed, public investors felt every dollar of pain. Today, when AI startups fail, the losses are absorbed by venture capital funds, their limited partners, and the employees holding illiquid equity. To further explain, these losses are now distributed among private investors rather than directly impacting the public market, so the public market never sees it.

Among the top companies today, Nvidia stands out as the world’s most valuable company, highlighting the global significance and dominance of AI industry leaders.

What This Means for Investors

Looking at the top 20 companies by market capitalization in December 1999 versus October 2025 reveals another structural shift. Technology companies represented 55% of the top 20 in 1999 and 75% in 2025. But only one company—Microsoft—appears on both lists.

The telecom giants that dominated 1999 (AT&T, Deutsche Telekom, MCI WorldCom, Nokia) have completely disappeared from the top 20. General Electric, the second-largest company in 1999, fell out entirely. The companies at the top today—Nvidia, Apple, Alphabet, Amazon, Meta—have spent decades proving their business models work.

This doesn’t mean AI valuations are rational or that a correction is impossible. It means the mechanism for a dot-com-style public market collapse has been dismantled. The speculation that would have created spectacular public blow-ups now lives in private markets with a much smaller audience for its failures. Much of the risk is now absorbed through complex finance and financial engineering, including private credit funds, SPVs, and securitizations that structure AI-related investments. Private equity has also become a major backer of AI infrastructure projects, providing large-scale funding through concentrated investment vehicles. In the broader financial ecosystem, Wall Street’s involvement—via securitizations and massive capital allocations—has played a significant role in fueling the AI investment boom and shaping market dynamics.

The AI bubble might be deflating right now. You just won’t see it in your 401(k) statement.

This article was originally published on CFOpro+analytics titled “Why the AI “Bubble” Won’t Pop As the Internet Bubble Did“

FAQ

Could AI failures eventually reach public markets?

Some AI-focused public companies could certainly see significant corrections if revenue growth disappoints or if the technology fails to deliver on its promises. However, the pure speculation—companies with no revenue, no business model, and no path to profitability—is largely contained in private markets. Public AI exposure is concentrated in established companies like Nvidia, Microsoft, and Alphabet that have diversified revenue streams and proven track records.

Why didn’t larger investment banks replace the CHARM Banks in taking early-stage companies public?

The economics don’t work. Bulge-bracket banks make money on large transactions with significant fees. Taking a $50 million market cap company public generates minimal revenue but creates substantial regulatory and reputational risk. The boutique banks specialized in these deals and built relationships with emerging technology companies. When they were absorbed into larger institutions, that expertise and risk appetite disappeared. The larger banks redirected their technology banking toward later-stage, larger transactions.

Does this mean venture capital investors will bear all the AI losses?

Venture capital losses ultimately flow through to the limited partners who invest in those funds—pension funds, endowments, foundations, and high-net-worth individuals. However, these investors typically have diversified portfolios and longer time horizons than retail investors in public markets. They also signed up for high-risk, high-reward investments. The systemic risk of AI speculation is therefore distributed across sophisticated investors with appropriate risk tolerance rather than concentrated in retail brokerage accounts and retirement funds.

At CFO Pro+Analytics, we partner with founders and owners to deliver clarity, confidence, and control. Together, we can design a roadmap that connects your ambition with a sound financial strategy.

CLICK HERE to schedule a free 20-minute consultation call

Leave a Reply